Phantom Time Hypothesis Unraveled: The Evidence Against Illig's Fabricated Centuries

The Phantom Time Hypothesis. It sounds like something ripped from the pages of a science fiction novel, doesn't it? But for a while, this fringe theory, popularized by Heribert Illig in the 1990s, gained a surprising amount of traction. The claim? That the years 614-911 AD were essentially made up, a historical sleight of hand perpetrated by the Holy Roman Empire, specifically involving figures like Pope Sylvester II and Emperor Otto III. It's a compelling idea, sparking intrigue and forcing us to question the narratives we take for granted.

But here at ConspiracyTheorize.com, we're not just about embracing the unusual; we're about rigorous examination. So, let’s put on our skeptical hats and delve into the historical and archaeological evidence that brings the "phantom time" crashing back down to earth. We will analyze why, despite its initial allure, this theory simply doesn't hold water under scrutiny.

The Foundation of the Phantom: Illig's Core Arguments

Illig's central thesis rests on a few key assumptions. He argues that:

- There is a lack of archaeological evidence and historical documentation from the period 614-911 AD, especially concerning Western Europe.

- The Carolingian dynasty seemingly appeared out of nowhere with advanced architectural and societal structures, suggesting a sudden leap forward uncharacteristic of organic development.

- The Gregorian calendar reform in 1582 "corrected" for a discrepancy that was, in fact, fabricated to legitimize the Holy Roman Empire's timeline.

- Emperor Otto III, allegedly motivated by vanity and a desire to rule in the year 1000 AD, orchestrated the entire fabrication.

Sounds convincing... until you actually start digging.

Architectural Evidence: The Stones Tell a Different Story

One of the most potent arguments against the Phantom Time Hypothesis comes from architecture. Illig claimed a lack of demonstrable construction during this period and attributed the Carolingian Renaissance to fabricated history. However, the archaeological record paints a vastly different picture.

Take the Palatine Chapel in Aachen, for example. Construction began around 792 AD under the reign of Charlemagne and was completed around 805 AD. This magnificent structure, a key example of Carolingian architecture, showcases a distinctive style blending Roman, Byzantine, and early Christian elements.

The stylistic continuity between pre-614 AD architecture (e.g., late Romanesque basilicas) and post-911 AD architecture (e.g., early Romanesque cathedrals) is demonstrable. Carolingian architecture sits firmly in between, exhibiting a clear progression in design and engineering. Dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) on wooden beams used in Carolingian structures consistently places them within the alleged "phantom" timeframe. These buildings didn’t magically appear; they were built, modified, and existed within a real, measurable timeline. The gradual evolution of arch styles, vaulting techniques, and decorative motifs directly contradicts the idea of a sudden, unexplained architectural revolution.

Coinage: Currency as a Chronicle

Coinage provides another robust challenge to Illig's claims. During the 7th to 10th centuries, numerous mints across Europe were actively producing coins. These coins often bear the names and images of rulers, along with dates or indications of their regnal years.

For instance, consider silver coins from the reign of Charlemagne (crowned Emperor in 800 AD). These coins, found across his vast empire, feature his name and titles, definitively placing him within the contested timeframe. Similar evidence exists for other rulers, such as the Lombard kings in Italy and various Anglo-Saxon monarchs in England. The sheer diversity of minting locations and the continuous operation of these mints throughout the period make the idea of a fabricated timeline implausible. If the years were fabricated, it would require an unprecedented level of coordinated forgery across numerous independent entities.

Written Records: More Than Just Religious Texts

Illig downplays the significance of written records, suggesting a scarcity that doesn't exist. While large-scale, comprehensive chronicles might be less common for certain regions during this period, a wealth of other written materials survive. These include:

- Charters and legal documents: These records detail land transactions, legal disputes, and administrative decisions, providing invaluable insights into daily life and governance.

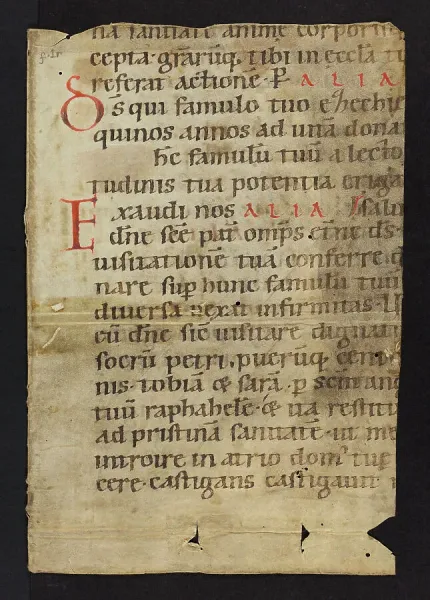

- Religious texts: While Illig dismisses religious texts, they often contain incidental historical information, such as mentions of contemporary events, rulers, and social customs. Furthermore, the development of script styles, such as Carolingian minuscule, can be traced through dated manuscripts.

- Commercial records: Trade flourished during this period, and merchants kept records of their transactions. These records, though often fragmented, provide further evidence of economic activity and social interaction.

Consider the historical figure of Alcuin of York (c. 735-804 AD), a prominent scholar and advisor to Charlemagne. His letters and writings provide detailed accounts of life in the Carolingian court and offer valuable insights into the political and intellectual climate of the time. The fact that his existence and activities are documented in multiple independent sources further undermines the Phantom Time Hypothesis.

Dr. Hans-Werner Goetz: A Leading Voice of Dissent

Historians have widely rejected the Phantom Time Hypothesis. Among the most vocal and articulate critics is Dr. Hans-Werner Goetz, a renowned medieval historian. Goetz has published extensively on the flaws in Illig's arguments, pointing out the selective use of evidence and the misinterpretation of historical sources. He emphasizes the demonstrable continuity in political, social, and economic structures throughout the period in question.

Goetz highlights specific examples, such as the consistent development of Frankish legal codes and the unbroken succession of bishops in numerous dioceses, as evidence against the notion of a fabricated timeline. His detailed rebuttals effectively dismantle Illig's claims, showcasing the robust historical evidence that supports the traditional chronology.

Flawed Assumptions: Where the Theory Goes Wrong

The Phantom Time Hypothesis rests on several flawed assumptions:

Misunderstanding Record Scarcity: Illig equates a perceived lack of specific types of chronicles with a complete absence of historical activity. However, history is not solely reliant on grand narratives. Archaeological findings, local records, and specialized documents provide a wealth of information about daily life, economic activity, and social structures, even in the absence of comprehensive chronicles. The idea that a "dark age" means a complete blackout of information is simply incorrect. Archaeological evidence provides insights into daily life and societal structure that written records often miss.

Misrepresenting Emperor Otto III's Motivations: Illig posits that Otto III fabricated the timeline to legitimize his rule in the year 1000 AD. This is a mischaracterization of Otto III's reign. Otto III was a complex figure deeply interested in Roman traditions and imperial revival. His motivations were driven by a desire to restore the glory of the Roman Empire, not to fabricate history for personal gain. The idea that he possessed the power and influence to rewrite almost 300 years of history across numerous independent kingdoms and principalities is simply ludicrous.

- Ignoring Other Calendars: The Phantom Time Hypothesis is largely Eurocentric and ignores the records of other regions and civilizations. The Byzantine Empire, the Islamic world, and civilizations in Asia all maintained their own calendars and historical records during this period. The theory fails to account for how these independent timelines would have been synchronized with the fabricated European timeline.

Conclusion: The Phantom Time Fades Away

The Phantom Time Hypothesis, while intriguing in its initial premise, ultimately crumbles under the weight of historical and archaeological evidence. Dated architectural features, coinage, written records, and the informed critiques of historians like Dr. Hans-Werner Goetz all point to the continuous and verifiable existence of the years 614-911 AD. The flawed assumptions underpinning the theory, particularly the misunderstanding of record scarcity and the misrepresentation of Emperor Otto III's motivations, further undermine its credibility.

It's important to remember that questioning established narratives is a crucial part of critical thinking. However, it’s equally important to ground our inquiries in evidence and sound reasoning. The case of the Phantom Time Hypothesis serves as a valuable reminder of the importance of verifying historical claims using primary sources, archaeological data, and expert analysis. While the idea of fabricated centuries might make for a captivating story, the reality, as revealed by the evidence, is far more compelling.