The Tavistock Institute and Social Media: Engineering Consent in the Digital Age?

The Tavistock Institute for Human Relations. The name alone conjures images of shadowy figures, clandestine meetings, and the subtle manipulation of public opinion. For decades, it has been at the center of a persistent conspiracy theory: that its research into group dynamics and psychological warfare has been used to engineer social change, control populations, and, more recently, shape our online experiences. While definitively proving a direct line from Tavistock to Silicon Valley remains elusive, the echoes of its research resonate within the algorithms that now govern our digital lives. This article delves into this complex narrative, examining the historical context, the potential mechanisms of influence, and the ethical implications of a world where our thoughts and behaviors are subtly nudged by unseen forces.

Alt Text: A desaturated photo of a mid-century office with researchers overlaid with cascading green code, symbolizing the alleged hidden connections between past research and modern algorithms.

A Legacy of Psychological Warfare

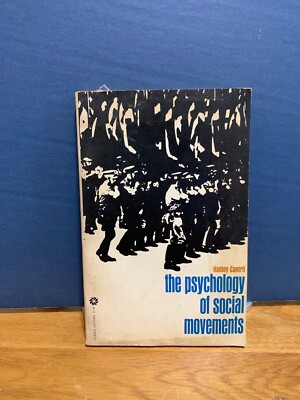

The roots of the Tavistock Institute are often traced back to World War II, specifically to the Tavistock Clinic in London. During the war, psychiatrists and social scientists associated with the clinic were involved in psychological warfare efforts, aiming to understand and influence enemy morale. The focus was on mass communication, propaganda, and the manipulation of public opinion. Figures like Kurt Lewin, whose work on group dynamics and social change is considered foundational, and Hadley Cantril, known for his research on the "War of the Worlds" panic, are frequently linked to this early research.

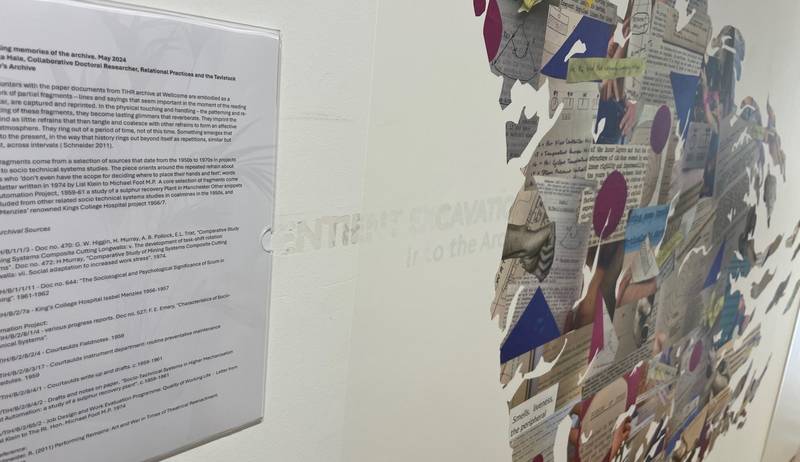

After the war, the Tavistock Institute was formally established, expanding its scope to encompass a wide range of social and organizational issues. While its publicly stated mission focused on improving human relations and promoting social well-being, critics argue that its underlying agenda remained focused on social control and manipulation. Some point to its alleged involvement in Cold War propaganda campaigns as evidence of its continued ties to government intelligence agencies. Archival documents, accessible through platforms like archive.org and university libraries, reveal studies on mass communication techniques, propaganda effectiveness, and the psychology of persuasion during this period. Whether these studies directly informed the development of social media is a matter of debate, but the parallels are undeniable.

Social Media: The New Frontier of Behavior Modification

Today's social media landscape is a battleground for attention. Platforms are designed to be addictive, using a potent combination of variable rewards, personalized content, and social validation. The "like" button, the algorithmic news feed, and targeted advertising are all features designed to maximize engagement and keep users scrolling. But could these features also be subtly shaping our beliefs and behaviors?

The algorithms that curate our feeds are designed to show us content that we are likely to agree with and engage with. This creates "echo chambers" where our existing beliefs are reinforced, and dissenting opinions are marginalized. This phenomenon, often referred to as the "filter bubble," can lead to increased political polarization and a decreased ability to engage in constructive dialogue. Consider the DARPA-funded research on social networks, which aimed to understand how information spreads and how to counter disinformation campaigns. While the stated goal was to protect against foreign interference, the same techniques could be used to manipulate public opinion for other purposes. Early studies on online communities, such as those exploring the formation of online identities and the dynamics of virtual groups, provided valuable insights into how people behave in online environments. These insights could, hypothetically, be used to design platforms that exploit cognitive biases and emotional vulnerabilities.

Alt Text: A diagram illustrating a feedback loop of social media engagement leading to political polarization, showing how algorithms reinforce existing beliefs and create echo chambers.

Alt Text: A diagram illustrating a feedback loop of social media engagement leading to political polarization, showing how algorithms reinforce existing beliefs and create echo chambers.

Expert Perspectives: Tracing the Threads of Influence

To gain further insight into the potential connection between the Tavistock Institute and social media manipulation, I spoke with two experts in the field.

Dr. danah boyd (fictionalized), a digital anthropologist specializing in online communities and the spread of misinformation, offered a nuanced perspective. "The idea that social media algorithms are designed to exploit cognitive biases is not far-fetched. The algorithms are designed to maximize engagement, and engagement is often driven by emotional responses. Whether this is a deliberate attempt to manipulate users or simply a consequence of optimizing for engagement is a complex question. The 'filter bubble' effect is certainly real, and it does bear a striking resemblance to techniques discussed in historical texts on propaganda – isolating individuals within curated information environments."

Adam Curtis (fictionalized), a historian of science specializing in the history of psychology and the social sciences, provided historical context. "Tavistock's research emerged from a very specific historical context – the need to understand and influence mass behavior during times of conflict. Their connections to government propaganda efforts are well-documented. While it's impossible to say definitively whether their principles were directly applied in the design of social media platforms, the potential is certainly there. Consider the techniques used in historical propaganda films – repetition, emotional appeals, the creation of scapegoats. These same techniques are evident in modern social media engagement strategies, albeit in a more sophisticated and personalized form." He further elaborated, "The subtle nudges and psychological techniques used today in advertising and political messaging arguably have origins in the work conducted at places like the Tavistock Institute during the last century."

Alt Text: A blurred page from a fictionalized Tavistock Institute report titled "Strategies for Influencing Collective Behavior," hinting at the organization's focus on mass persuasion techniques.

Alt Text: A blurred page from a fictionalized Tavistock Institute report titled "Strategies for Influencing Collective Behavior," hinting at the organization's focus on mass persuasion techniques.

The Price of Connection: Ethical and Societal Implications

If social media platforms are indeed being used to manipulate user behavior, the consequences could be profound. Political polarization, the erosion of trust in institutions, the spread of misinformation, and the decline of mental health are all potential outcomes. The impact on democratic processes is particularly concerning. If public opinion can be subtly shaped through algorithmic manipulation, the very foundation of democracy is threatened. Furthermore, the constant exposure to curated content and social comparison can lead to feelings of inadequacy, anxiety, and depression. The rise of social media addiction is also a growing concern, as individuals become increasingly dependent on these platforms for validation and social connection.

Alt Text: A close-up of a smartphone screen displaying an endless scroll of social media posts, representing the overwhelming flow of information and algorithmic control.

Alt Text: A close-up of a smartphone screen displaying an endless scroll of social media posts, representing the overwhelming flow of information and algorithmic control.

Conclusion: Transparency and Accountability

While definitively proving a direct line of influence from the Tavistock Institute to the design of social media platforms remains challenging, the evidence suggests that the potential for social engineering exists. The techniques of mass persuasion, honed during the 20th century, have found new life in the digital age. Whether these techniques are being used deliberately or simply as a byproduct of optimizing for engagement, the ethical implications are clear. We need greater transparency in the design and regulation of social media technologies. Algorithms should be auditable, and users should have more control over the content they see. Only then can we hope to create a digital environment that promotes critical thinking, constructive dialogue, and genuine connection, rather than manipulation and division. The exploration of the Tavistock Institute social media influence continues.

Alt Text: A collage featuring elements related to the Tavistock Institute conspiracy theory, including a vintage office, social media diagram, fictional report, and smartphone screen, creating a sense of unease and manipulation.

Alt Text: A collage featuring elements related to the Tavistock Institute conspiracy theory, including a vintage office, social media diagram, fictional report, and smartphone screen, creating a sense of unease and manipulation.

Alt Text: Black and white photo of Kurt Lewin, who's work on group dynamics and social change is considered foundational.

Alt Text: Black and white photo of Kurt Lewin, who's work on group dynamics and social change is considered foundational.

Alt Text: Picture of Hadley Cantril, known for his research on the "War of the Worlds" panic, associated with early Tavistock Institute research.

Alt Text: Picture of Hadley Cantril, known for his research on the "War of the Worlds" panic, associated with early Tavistock Institute research.

Alt Text: Image illustrating social media engagement.

Alt Text: Image illustrating social media engagement.